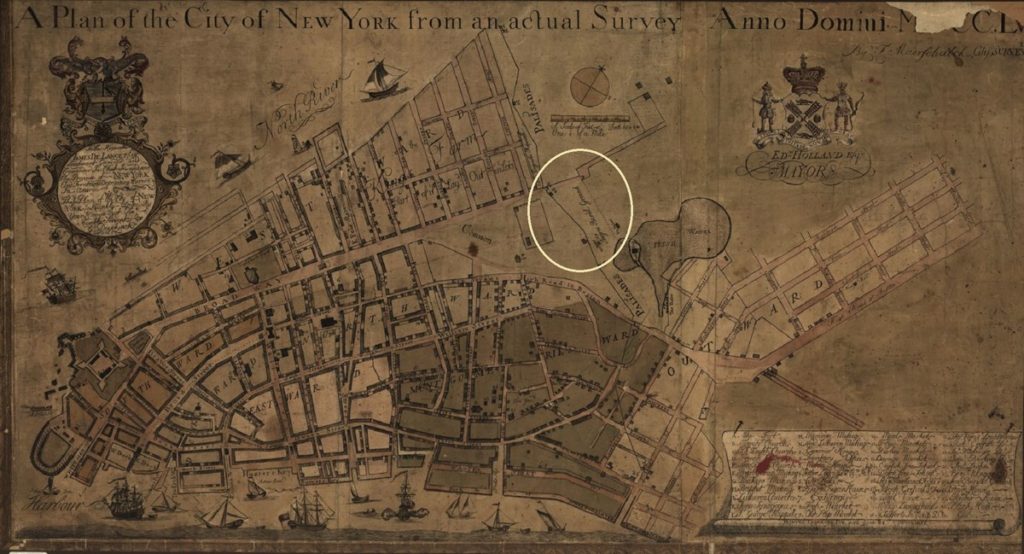

How often does an archeological discovery turn on its head everything we thought we knew about a particular place? In 1991, in the process of excavating land in lower Manhattan for a new Federal building, a historic burial ground was found lying 30 feet beneath the well-trod city streets. Stretching across 6 acres adjacent to the present day location of City Hall, the land holds the bodies of at least 15,000 enslaved and free Africans, buried by family members and friends from the 1630s until 1795.

The discovery led to a years-long effort by local and international African diaspora communities, united with historians archeologists from major universities, to halt construction on the land until excavations and research could be completed.

Initially established outside the original city limits due to a prohibition against burying anyone of African descent in the Trinity churchyard cemetery, use of the grounds continued for generations. For this reason, researchers who have studied the excavated remains have been able to greatly deepen our understanding of slavery in New York City, and learn about the lives and traditions of the many enslaved and free Africans who resided in Manhattan during the 17th and 18th centuries.

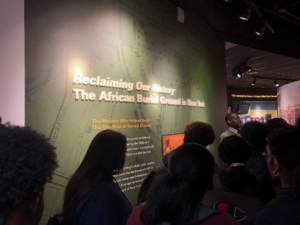

Now, the burial ground is marked with a National Parks Service memorial and museum, where several excavated bodies have been re-interred in a traditional ceremony. The site is considered to be one of the most significant urban archeological discovery of the 20th century.

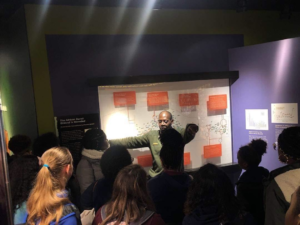

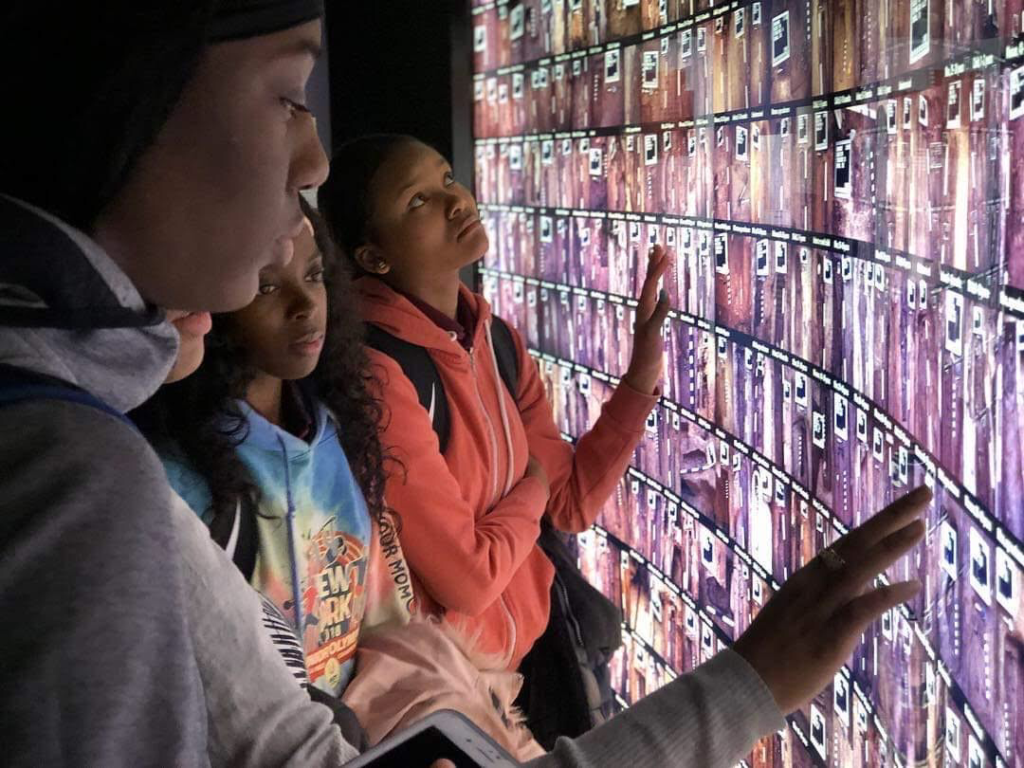

When our students visited this site they were struck by the fact that such an astounding historical reality resided just beneath their feet as they walked the blocks between Broadway and Chambers street that mark the periphery of the grounds. Led by a helpful tour guide, they examined the many artifacts and models present in the museum, and read from letters and original documents relating to slavery in the period. Perhaps most striking, however, were the photos of hundreds of excavated bodies, ranged from just-born infants to elderly persons.

Many students expressed surprise to learn that something of such profound historical significance had been buried for centuries beneath a constantly growing, expanding and changing city. When so much of what we remember from the past relates to famous and powerful figures, it is crucial to pay attention to the regular people, ancestors of so many of us, whose daily lives made up the vast majority of what happened. We hope that you have the chance to visit this museum and take a look for yourself!